Close

Juana Elena Diz, born in 1925 in Buenos Aires, Argentina was the only woman of the Spartacus Group, which lasted from 1959-1968. Members of the group included Esperilio Bute, Ricardo Carpani, Pascual Di Bianco, Raul Lara Torrez, Mario Mollari, Juan Manuel Sánchez, Carlos Sessano and Franco Venturi. At a time when ladies in Argentina did not occupy a relevant place in art, Diz was not only part of the group but portrayed female characters in her work.

Painter, engraver, and ceramist, Diz graduated from the Manuel Belgrano School of Fine Arts and attended the Vicente Puig workshop. She joined the Spartaco Group in 1960 and participated in all exhibitions until its dissolution in 1968. Between 1975 and 1976 she resided and worked in the Balearic Islands. Her works are included in numerous institutions and collections, among which are the Vancouver Art Gallery, Simon Fraser University (Canada), and in Argentina the Museum of Fine Arts of Santa Rosa, the Museum of Modern Art, and the National Museum of Engraving. As a muralist, she worked at the Light and Strength Union of Mar del Plata (Argentina) and in several private buildings.

After her journey with the Spartaco movement, her biography was truncated forever: she went away from everyone without leaving traces of her whereabouts. Even today, her family does not know whether or not she is alive. Although several hypotheses surround her disappearance – the strongest one is related to her joining and becoming a member of a cult – though these have never been discussed. Her destiny is an enigma, and her only trace remains her work.

The irruption of an artistic group with social interests was a historical landmark in the Argentinian art scene. Spartacus functioned as an artistic and political unit, with its own manifesto, until the ideological frictions and the place occupied by her works in the art market determined its dissolution. Paradoxically, they had been institutionalized by the same system that they opposed and their works were listed in the market.

With the strong influence of Mexican muralism and the expressionist drama of the Brazilian Cándido Portinari, Spartacus set out to create, with monumental figuration, a revolutionary art that played an active role in local politics. Two of its members later joined the union militancy.

They admired Jose Clemente Orozco, Diego Rivera, Rufino Tamayo, and Oswaldo Guayasamín because “coming from the very roots of reality they had engendered an art of universal transcendence.” With a synthesis between realism and abstraction, Spartacus managed to renew the Americanist tradition of Mexican muralism. Its objective was to create a national art that surpassed the local borders until anchoring in Latin America. In that way, they opposed non-figuration and costumbrism or pictorial folklorism. They also faced the artists of the avant-garde Di Tella Institute. While they prioritized the social function of art, they also ventured into traditional subjects such as landscapes, nudes, and portraits, sometimes leading to unique experiments.

With the new art, they were pushing for unity in Latin America that, they said, had not yet been achieved in the political arena: “Art is the liberator for excellence, and the multitudes recognize themselves in it,” they maintained. They had no doubts: from the new generations of artists and art with a Latin American stamp would emerge: art would precede and give impetus, thus, to the political unity they longed for in the South.

In their manifesto, they raised the need for a “transcendent plastic expression: a defining feature of our personality as people.” They asserted that “an economy alienated from the foreign imperialist capital only originated cultural and artistic colonialism.” That is why they promoted national art. Works of art had to be – and embody – a social and national expression at the same time: they thought that through the great creations of the History of Art it was possible to perceive “the spirit of the society that begets them.”

With desaturated colors, as well as strong and solid shapes, they created an iconography of the peasantry proud of their work and the industrial workers amid factory landscapes. They were convinced of the radical power of art. Revolutionary art had to emerge as a monumental and public expression outside the circuit of museums, halls, and galleries. They sought to democratize culture: they painted walls of unions and shared walls (although they weren’t always able to do so), made posters that came to the hands of the workers, and painted works in universities, where the student movement grew. In their manifesto, they wrote: “Of the easel painting, as a luxurious solitary vice, we have to pass resolutely to the art of masses, that is, to the art.”

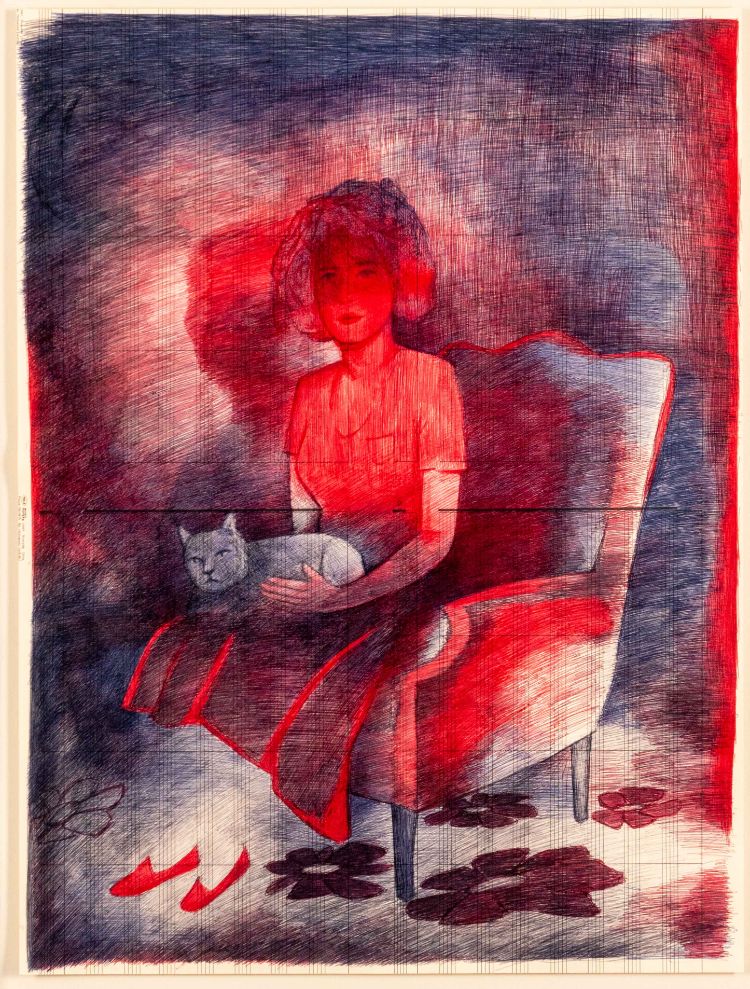

Some images became an emblem of time: with an economy of formal and pictorial resources Diz, like the other members of Spartacus, placed the subject to which the work alluded to in the foreground. Their things were the geometric figures – in some cases monumental- and made of stone, and the synthesis of lights and shadows.

Spartacus did not conceive the artist in a place of ostracism or pure individual experience. Moreover, they considered that artists who did not take into account the struggles of the Latin American worker emptied their work of content, “castrating it of all significance.” Although the work could be virtuous regarding technique, and even capable of reaching an exquisite bill, it was worthless if it was not strongly anchored in reality. For them, art was “a combat weapon” that the artist could use to reflect his society, “not as a mirror but as a modeler.” Both the artist and the characters portrayed were considered active social subjects and artificers of change: the revolutionary utopia.

In a silent climate where time is stopped, Diaz uses her work to focus on the general solitude of the indigenous women. It is not easy to find male figures in her paintings. One of the exceptions is a nude of a pair of young lovers: the forcefulness of these geometric and solid figures reinforces the stillness of that encounter. Sitting side by side, hugging tenderly, their eyes do not cross.

Diz prefers earth tones, although sometimes the light and bright colors burst. In her works, one encounters working women; mothers with their children in their arms (some of them remind some of the representations of child Jesus with an adult body in Byzantine style). Mujer con Choclos (oil canvas, 1966) is one of her key works: a woman carrying corn, a key food constituent in Latin America, in communion with her land and nature. Some ladies comb their hair; many look like anthropomorphic figures: the face and feet become strange, disproportionate. Whether dressed, naked, in the living room, in the courtyard, on balconies, alone or in groups of two or three, they all have something in common: as she says, these women are a pure enigma.

They do not look at each other, and at the same time, they all evade the viewer’s gaze. They seem self-absorbed, locked in their thoughts, their memories. Submerged in secret dreams. Even when they look directly at the viewer: their eyes, completely black, are like an indecipherable veil. One cannot help but wonder what these women think. What is it that captures them with such intensity?

From 1960 – 1968, she participated in all Grupo Espartaco exhibitions

Be the first to know about new arrivals and promotions