Close

Merely at the age of 14, Raul Conti felt that his path was towards the arts: he consulted with Juan Grela if would be willing to teach him to paint long before the teacher thought about teaching. Conti had to insist until he became Grela’s first disciple. “Grela taught me to look” he recalls. Later, due to his bond with him, he met Berni and the Litoral Group (composed, among others, by Grela and Leónidas Gambartes). The young Conti went to meetings with writers, poets, and other artists in the basement of a boxing club. “They influenced my thinking: all of them were strong and intellectual,” recalls Conti.

At 16, Conti traveled alone to Buenos Aires; he worked in a shoe heels factory. But his thing, his great passion, was art. He did not hesitate: he readied his small suitcase with paints and brushes, his folding easel, and a sling (if he couldn’t find work, he planned to feed with birds) and embarked on a journey with an uncertain destiny.

When he reached Corrientes, the lush and exotic nature, the lapachos mixture of flowering, hyacinths, herons, monkeys, iguanas, and alligators, dazzled him to the point that he remained to live in that place and started a family. In Itatí, a town where electricity was only available for a few hours each day, he devoted himself to restoring and modeling religious images of plaster and wood.

There were several trips in the artist’s life. For six months, he toured Bolivia, Peru, Panama, Colombia, Ecuador, and Mexico: a key experience in his life and his work. While visiting museums and ruins, he studied pre-Columbian cultures. “I wanted to investigate my roots,” he recalls. Amphoras and tissues fascinated him, “For me -he notes- condense the meaning of the word culture: cultivating knowledge (modeling, cooking, sewing or varnishing) from generation to generation to make a unique piece.” He adds: “Knowing the pre-Columbian cultures changed my point of view: so far, he only had in mind the map of Europe.”

From pre-Columbian cultures, he included in his works the horizontality that dominates the composition (the dynamism of its images is minimal); rectangular heads; earthy tones; figures’ frontality, and the flatness of the images.

With a strong symbolist imprint, Conti reinterprets the pre-Columbian cosmogony. In his paintings, sculptures, engravings, and aero tints, he adds legends, myths, and popular culture. He represents hands with four fingers in allusion to the first woman who was ever created in Tiahuanaco, which had that predominant characteristic, having emerged from fire. Conti integrates this belief with his own symbolism. “For me, it alludes to the generosity: with four fingers, you can give; but without the prehensile finger, you can never take away,” he explains.

The ovoid shape (symbol of biological gestation and ideas) appears crossed –sealed- by two diagonals that symbolize the cruel execution of Tupac Amaru, Inca chieftain who led the fight to liberate the peoples of South America from the Spanish crown.

Like many pre-Columbian cultures, in Conti’s paintings, frogs symbolize fertility; owls symbolize supernatural forces. “In most northern communities of Argentina, these animal feathers are considered to have hypnotic powers and are used to attract the loved one,” says Conti.

In 1977, Conti settled with his family in New Jersey. Then, they moved to New York, Hell’s Kitchen, a neighborhood that, as the artist recalls, was dominated by the mafia, drugs, and prostitution. In his works of that time, characteristics such as buildings’ fire stairs, and traffic signals of the city that had moved, and where he stayed until 2012 can be observed. Today, he lives between New York and Buenos Aires.

Regarding the Latin American artists who roamed around the streets of Soho, Village, and Chelsea, Conti represented them “like birds, (immigrants) of the heavy flight which cannot settle, nor fly really high.”

Conti exhibited in museums, galleries, and cultural venues in the United States, Sweden, Argentina, Bolivia, Ecuador, Mexico, Panama, Colombia, Spain, and Puerto Rico. His work is exhibited in public and private collections in America and Europe.

Conti is concerned about the society in which he lives: not only included social conflicts that cringe in his works, but also the ones he actively participated in. In the eighties, he joined with other artists and a group of doctors in a program to help homeless and ex-convicts on the outskirts of Manhattan out of drug addiction through art. The project was a success; 400 people joined.

When Argentina’s military dictatorship was still suffering, Conti made a poster to promote the celebration of the International Week of the Disappeared (May 1983 in New York), which represented the struggle of the Mothers of Plaza de Mayo. “Of course, for those times, I was anonymous; then, the Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo took it as a cover of her diary, and the same theme is used around the pyramid of the Plaza de Mayo in Buenos Aires,” said the artist.

In his recent works, Conti puts picker guys on center stages (the representation preserves prehistoric symbols) that go with their cars in Buenos Aires. With the city’s maps marked throughout the body, they roamed looking for cardboards and papers to recycle. Zoila, Juanita, Chicharrita, and his brother have his mouth covered with tape, like those used to gag. “I did so because they have no voice or vote,” Conti says. There is much sadness in the eyes of the little pickers. Heterodox artist, Conti made from engravings and subtle aero tints on paper to cast sculptures in Quebracho Colorado, cinchona (sometimes polychromed), yellow oleander, aluminum, marble, bronze, and iron. Some of these pieces bear strings: they are musical sculptures; in other cases, the artist incorporates his sculptures with pieces of pianos.

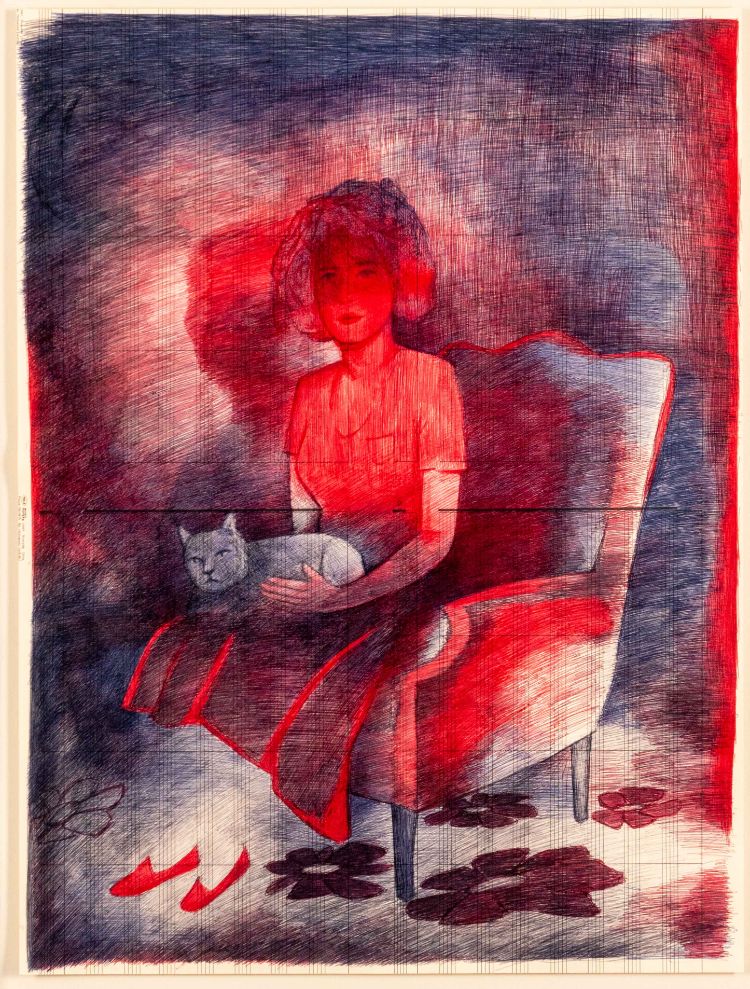

Guardián de Signos (Oil, 1974), Vida (oil, 2001), Curandero (quebracho, 2000), El Curandero con el Búho (quebracho, 2002) combine large number of symbols. Among his notable works, include Los Pintores (oil on hardboard, 1964), La Señal (oil, 1976), La Espiga (oil on canvas, 1979), Iberá Sun (carob, 1998), Hechizo (oil on canvas, 2010) , Colores Guardados (oil on canvas, 2012), La Garza de tus Sueños, (diptych, oil on canvas, 2013), Blanca Blusita de Algodón, Cabello Negro y Escribe Poemas (oil on canvas, 2013), Viento Cálido del Norte ( oil on canvas, 2015), La Isla Pacurí (oil, 2015).

In Paleta encendida, a painter (who could be the alter ego of Conti) prepares a fascinating blue, a jewel that illuminates the canvas and captures the viewer. It is a work that integrates a series in homage to the artists who follow their passion, though not achieving any recognition on its own.

Today, Conti’s painting is lit. It’s brilliant. The creations of this octogenarian artist have the power of a young painter. His characters, which retain some the statism, silence, and flatness of their pictures with a pre-Columbian seal, become to others. They look like something out of an oriental comic and inhabit a strange and exuberant universe, such as the artist saw near the shrine of Our Lady of Itati, in Corrientes, when first launched himself into the art world.

Reference:

-Raul Santana, Raúl Conti. Raúl Conti. Sixty years of paintings and Sculptures. Malmo, Sweden: World Print SA, 2004.

– Greger Olsson, Raul Conti, Raul Conti, My life – my Works. Florida (Buenos Aires province): AGI – Integrated sa Graphic Arts, 2014.

– Raul Conti Retrospective 2016 (Art & Art Gallery, Miami, USA). Miami: Art & Art Gallery, 2016.

– http://www.raulconti.com/indexEsp.html

AWARDS:

None because he never presented to classrooms or contests

EXHIBITIONS:

Exhibited in museums, galleries and cultural venues in the United States, Sweden, Argentina, Bolivia, Ecuador, Mexico, Panama, Colombia, Spain and Puerto Rico. His work integrates public and private collections in America and Europe.

Be the first to know about new arrivals and promotions